Lessons Learned from the OpenADMET - ExpansionRx Blind Challenge

Maria Castellanos Hugo MacDermott-Opeskin Jon Ainsley Pat Walters

The ExpansionRx challenge, launched on October 27, 2025, closed two weeks ago! We are extremely grateful to everyone who participated and made this incredible learning experience possible for the ML and ADMET communities. After releasing the final leaderboard in our previous blogpost. Now we’re going to dive deeper into the models used by the top-performing participants. We would also like to acknowledge an excellent writeup by Vlad Chupakin, which ended up being quite similar to our own!

Participants used a wide range of methods

With 370+ participants and more than 1000 total submissions, the challenge was a massive success! More importantly, we are impressed by the broad range of methods and techniques the challenge participants explored. In the table below, we summarize the trends observed for the top 20 participants in selected categories:

- Model type: Which model (or ensemble of models) was used

- Data preparation: Was the model trained from a pre-trained model? Was external public data used? Was proprietary (Prop.) data used? Which descriptors were chosen? Was a multi-tasking approach chosen? Was data augmentation used on the training data?

- Training: Which split strategy was used for internal validation, and whether Hyperparameter Optimization (HPO) was used.

- NM = not mentioned.

Multitask GNNs were the undisputed winner of the challenge

2D Graph neural networks (GNNs) dominated the top of the leaderboard. In particular, Chemprop proved a popular choice among participants, with its ease of use, suitability for multitasking learning, and ability to incorporate additional features likely contributing. Other participants used the KERMT architecture from Merck and NVIDIA, as well as Uni-Mol, with some success. TabPFN was also popular but ultimately lacked the performance of 2D GNNs at the top of the leaderboard. Multitask learning was essential, with several top-performing groups also investigating the placement of tasks into related groups (task affinity groups) where they could complement each other, a strategy that has previously proved successful in literature [1][2].

Some top performers also used model ensembles to enhance performance, ranging from simple averaging to complex ensemble creation via the Caruana method or snapshot ensembling. Notably, a few participants also opted for hybrid ensembles of deep learning and classical ML models (including Random Forest, LightGBM, XGBoost, and CatBoost). These hybrid models show a lot of promise, with three out of the top 10 participants combining traditional ML with MPNN models, including campfire-capillary (ranked #4).

Pre-training and data augmentation helped

Many participants used pre-training to enhance their performance and improve generalisation. Pre-training strategies are generally aimed at enhancing a model's understanding of chemistry, separate from the specific training set in question. The use of the CheMeleon foundation model was popular, as was de novo pretraining of Chemprop.

Additionally, many teams used feature engineering, introducing features such as fingerprints, descriptors, more complex graph featurization, and quantum-mechanical or MD-derived properties. RDKit and Mordred descriptors were a popular choice due to their ubiquity and ease of use, while many participants also added electrostatic descriptors from the Jazzy library.

Several ingenious approaches even used de novo generation of molecules from the chemical space around the challenge molecules to augment pretraining sets. Some successful approaches for data augmentation included RIGR and SMILES enumeration, while some participants even generated molecules de novo.

External data was key to elite performance

Almost all top-performing entries used external data to augment the training set provided with the challenge. While the use of publicly available data was nearly universal, 4 of the top 5 participants also utilized proprietary data. While excellent performance can be achieved without access to proprietary data (kudos to those teams!), the ranking at the top of the leaderboard lends credence to the "more is more" narrative for machine learning in drug discovery and highlights the need for additional large-scale public data initiatives. Pre-competitive efforts such as OpenADMET aim to change this by collecting and disseminating high-quality ADMET data. Several federated learning platforms and cross-pharma collaborations have also sought to “de-silo” corporate data for shared benefit.

Popular choices of public datasets among participants included the ASAP Discovery x Polaris x OpenADMET dataset, Galapagos’ and Novartis datasets, ChEMBL, and Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC).

Hyperparameter optimization wasn’t very effective

While hyperparameter optimization is often touted as essential in deep learning, it took a back seat this challenge. Some top-performing entries performed extensive hyperparameter optimization, however most noted minimal performance gain or did not extensively tune their models. While difficult to separate, leaderboard trends suggest that additional data, data engineering and feature augmentation proved more impactful.

Assessing performance internally was critical

Internal performance assessment was a critical differentiator for success in the challenge. Several top-performing participants prioritized temporal splits to evaluate their models. This approach directly mirrors the prospective nature of the task at hand: predicting late-stage molecules from early-stage data. Random splits were also a popular choice, while multiple participants opted for scaffold splits to capture variability across distinct chemical series. Notably, shin-chan, opted for a more unique strategy, using difficulty-based splits, holding out molecules that were “hard” for the model to learn to ensure robust validation against more challenging chemistry. Several participants noted that metrics from internal cross validation and evaluation did not correspond to leaderboard performance, suggesting that the test set was sufficiently challenging to participants.

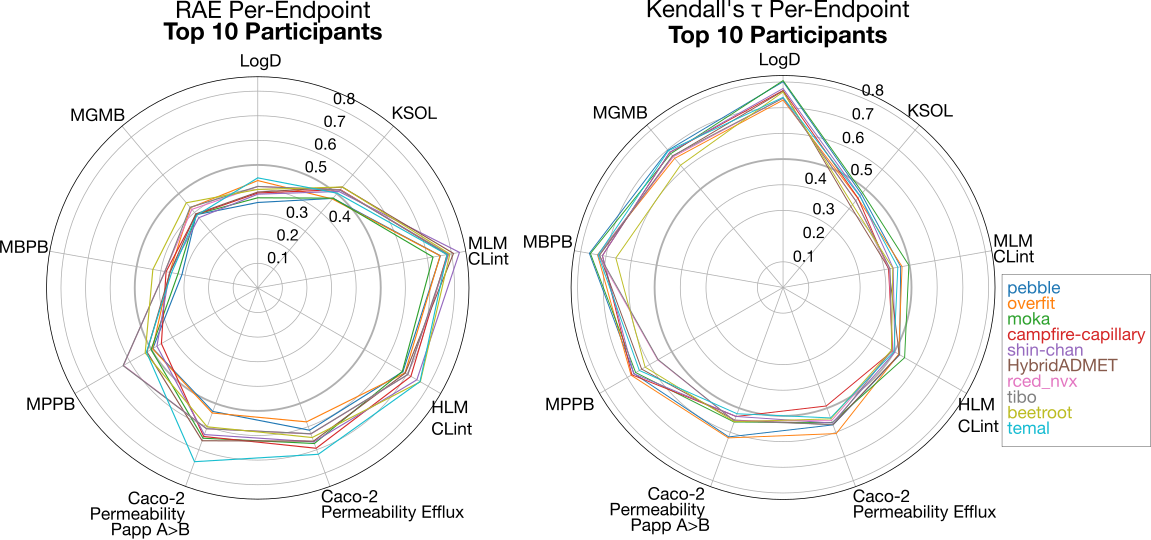

Per-endpoint performance

The overall performance varied significantly across the different endpoints. We show a radial plot with the distribution of RAE performance for the Top 10 participants (left). For most of the top-performing participants, LogD, KSOL and the Protein binding endpoints (MPPB, MBPB, and MGMB) seemed to be the easiest to predict in relative terms, while the clearance endpoints (MLM CLint and HLM CLint) and Caco-2 permeability endpoints consistently showed high error across the participants. Analysis of ranking ability with Kendall's tau reveals that the LogD and protein binding models had strong ranking ability, while ranking ability for KSOL, clearance and Caco-2 permeability was weaker.

Below, we further analyze the performance per-endpoint, by grouping into endpoint groups. Note that similar endpoints had comparable performance, which is both a reflection of data available, in the training set and from external sources, as well as the task-affinity grouping strategy that was used by the majority of the top performers.

LogD and KSOL

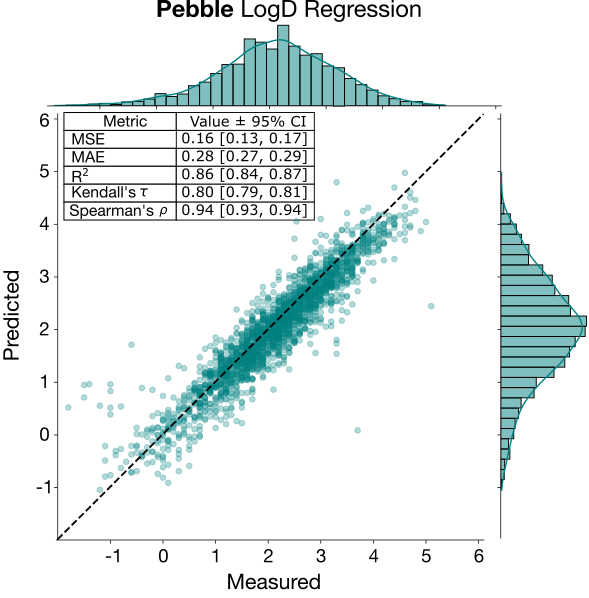

These two endpoints were the most represented in the training set, and generally have the most available public data, so one naively could expect performance to be better for these two. LogD prediction was excellent both in relative terms (RAE) and ranking (Kendall’s tau). This result was expected and reflects the abundance of external—public and proprietary—training data for this endpoint. LogD is known to be a relatively "learnable" property because it's largely additive. Contributions from molecular fragments sum predictably, and those same fragments tend to contribute similarly across different molecules. This contrasts with properties like solubility, where fragment contributions are less transferable and the overall property emerges from more complex, non-additive interactions.The excellent performance of the LogD regression model for the top performer, pebble, is shown below.

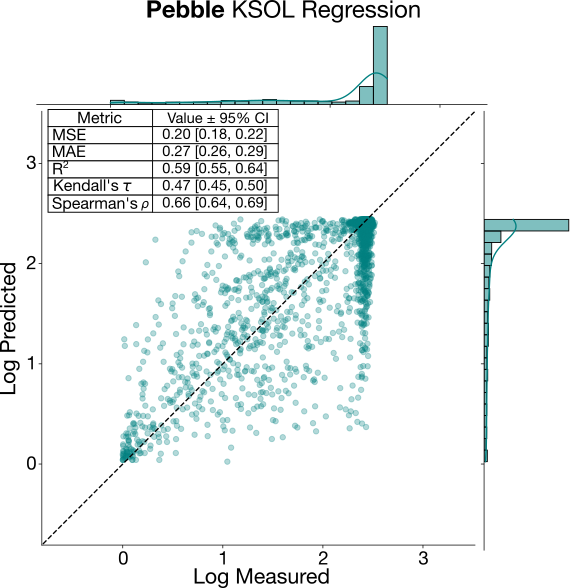

On the other hand, KSOL exhibits a decent relative performance, but poor ranking ability. While the data volume for this endpoint is comparable to that of LogD, KSOL is generally considered more challenging to predict across diverse chemical series [3]. It seems that the KSOL models were able to capture the global average solubility of the molecules, but were unable to rank the molecules prospectively. This difficulty is compounded by the highly skewed distribution of the data, with most molecules in the training and test set either falling into the “high-solubility” (median > 200µM), or “low solubility” threshold (<5 µM), leading to a large dynamic range (stdev of 0.7 in log scale). In such a “clumped” distribution, it is likely models are acting as binary classifiers (i.e., distinguishing between “soluble” vs “insoluble”), but lack the resolution to differentiate between compounds within the highly soluble cluster. Similar behaviour was observed in the recent ASAP Discovery-Polaris Antiviral competition, with KSOL proving easy to predict in relative terms, but with poor ranking performance. After examining the regression plot for KSOL below, the model performance is evidently poor, with a tendency to collapse predictions toward the distribution’s extrema rather than capturing meaningful structural-activity relationships.

Metabolism: MLM CLint and HLM Clint

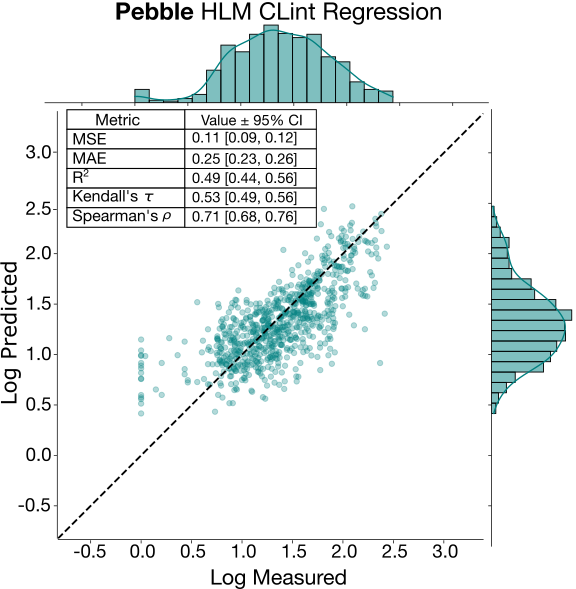

The intrinsic clearance endpoints (CLint) proved the most challenging tasks for participants, both in terms of relative error and ranking ability. Despite being well represented in the training set, and supplemented by public data (for example, in the ASAP-Polaris dataset), intrinsic clearance is notoriously difficult to predict, especially from public data [4]. This is mostly due to its sensitivity to small structural changes, making it difficult for models to generalize. The regression plot for pebble’s HLM CLint model is shown in the plot below. While the low MAE suggests good absolute performance, intermediate Kendall’s tau and R2 reveal that the test set molecules are still challenging for the model despite the test set being largely within the same chemical space. Similarly to KSOL, both MLM and HLM CLint exhibit a large dynamic range (stdev in the log scale is >0.6 for both), but with most compounds falling in the moderate to high clearance threshold. Notably, the regression plot shows that the model struggles to accurately predict low clearance molecules; these are more predominant in the test set as clearance became more “solved” towards the end of the discovery program (data not shown).

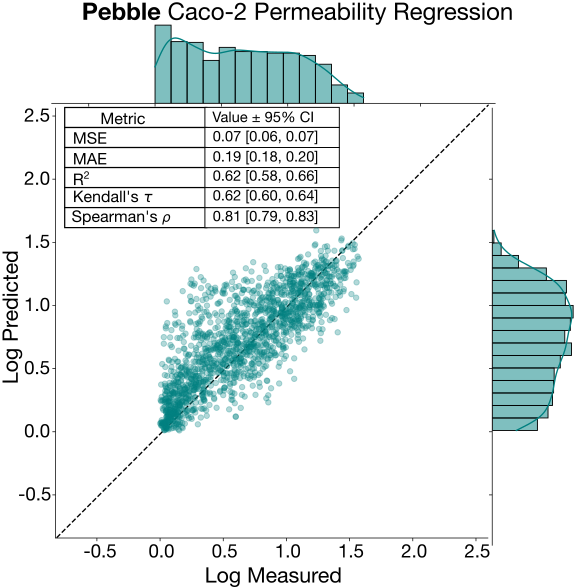

Caco-2 permeability

Caco-2 apical to basolateral permeability showed similar performance characteristics in between top performing endpoints (LogD and protein binding) and the more challenging clearance data, with high relative errors and moderate ranking ability. Notably, the performance delta between the top two contestants and the rest of the top 10 was large here. While obtaining Caco-2 permeability data is common in drug discovery campaigns, there is a paucity of high-quality, consistently generated public Caco-2 data. Though not separable from other factors, we suggest that this large delta may be attributable to the use of well-processed proprietary training data by the top two contestants. While passive permeability is strongly correlated with lipophilicity (and thus relatively learnable), compounds with high Caco-2 efflux ratios are subject to active transport by efflux proteins such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp). Predicting efflux is inherently more challenging: transporter recognition depends on specific three-dimensional pharmacophoric features and binding site complementarity rather than simple additive molecular properties. This makes efflux substrate recognition less generalisable across chemical series compared to passive diffusion. Caco-2 efflux ratio showed similar trends to Caco-2 permeability, but with less divergence between the top two contestants and the rest of the top ten.

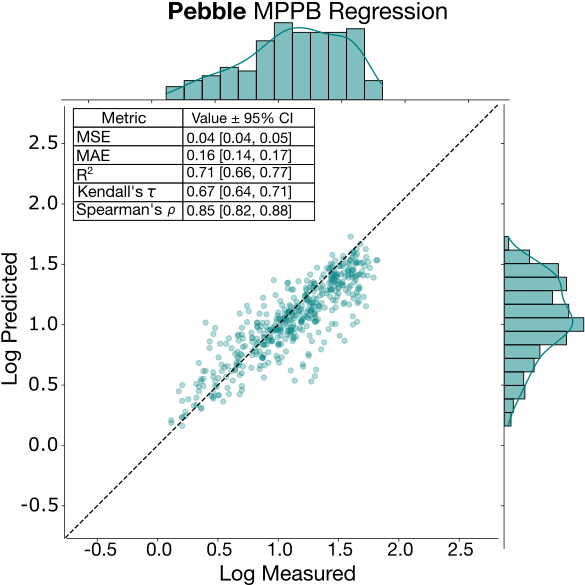

Protein binding (MPPB, MBPB and MGMB)

The three protein binding endpoints demonstrated robust performance across both error-based and rank-based metrics, despite being the least represented endpoints in the training and test set (and being somewhat more “niche” in the case of MBPB and MGMB). Several factors contribute to their good performance. First, while all three of these endpoints have a small dynamic range (~0.4 stdev on log scale), the data is evenly distributed across that range without the significant “clumping” observed with KSOL. The distribution can be appreciated in the MPPB regression plot below, which also shows a lack of significant outliers, leading to satisfactory correlation and error metrics.

Furthermore, protein binding is directly correlated to lipophilicity and size, which suggests a similar performance profile to the LogD models. In fact, a few top participants utilized multi-task learning strategies to train protein binding and LogD models together, allowing the binding models to take advantage of the high-quality feature representations from the larger LogD public datasets. Unlike intrinsic clearance, protein binding is less sensitive to minor structural shifts, making these endpoints easier to predict even within chemically diverse datasets.

We have now updated the per-endpoint leaderboards in the Leaderboard tab of our Hugging Face space to reflect the results evaluated in the full dataset.

Community Feedback (so far)

We appreciate the feedback everyone shared in the Google Form (you can still leave feedback if you haven’t already). We will do our best to learn from it and make the next challenge even better. The survey highlighted several positive aspects of this effort.

High-Quality Dataset: Participants praised the "large yet undisclosed dataset" and its diverse endpoints. The time-based train-test split was described as a "realistic" and stimulating aspect of the challenge.

Strong Community and Support: The Discord server was frequently cited as a major success, fostering "vibrant discussions" and a "friendly and welcoming atmosphere." Organizers were commended for their responsiveness to questions and issues. Our team truly enjoyed the engagement on Discord, and we plan to continue it.

Educational Value: Many users reported that the competition pushed them to innovate and try new architectures they otherwise wouldn't have explored. One participant called it a "massive success" that helped everyone learn.

Organization: Despite technical hiccups, the overall organization and execution were described as "excellent" and "top-notch."

Of course, there were also areas where we could have done better. We appreciated the constructive feedback and will work to address everyone’s concerns.

Submission System Instability: The most frequent complaint concerned the Hugging Face submission interface. Users reported the system was often slow, lacked progress bars or status updates (leaving them unsure whether a submission worked), and occasionally failed entirely. Some users spent hours trying to submit entries on the final day because of server instability. We feel your pain; the server issues were equally stressful for us. We underestimated participation and didn’t scale the server hardware appropriately. We’ve learned from this and will spend time between now and the next challenge to ensure a robust submission system that can handle the load.

Leaderboard Issues: Participants noted latency between submissions and leaderboard re-ranking. Some felt the leaderboard scoring lacked sufficient detail on relative scores across different prediction categories. As noted above, we acknowledge this issue with leaderboard latency and the information displayed. We are developing alternatives and plan to solicit community feedback in the near future.

Fairness and Submission Limits: Several participants felt that teams had a "disproportionate advantage" over individuals because they could submit more attempts to probe the test set. There were multiple requests to limit the maximum number of submissions per user or team to prevent a "deadline rush" and leaderboard climbing. We tried to balance the need for fairness with our desire for a compelling leaderboard experience. To do this, we used half the test set to generate real-time leaderboard rankings and the full test set to produce final rankings. We believe this strikes the right balance, but we are exploring additional measures to deter leaderboard hacking. One interesting suggestion is to list the number of submissions for each participant on the leaderboard.

Lack of Transparency on Data Use: Some participants requested that future leaderboards clearly distinguish between models that used only the provided data and those that used external or proprietary data. Others suggested that use of proprietary external data should be restricted altogether. While it’s good to indicate whether internal data was used on the final leaderboard, we’re not convinced that adding this to the real-time leaderboard would be beneficial. Restrictions on the use of proprietary data are impractical to enforce and in our opinion reduce learnings available from the challenge although this is certainly debatable.

Next steps

We hoped you enjoyed participating in this challenge as much as we enjoyed hosting it! Here’s what to look out for:

-

We will host a series of webinars, during which the top participants may present their work and results if they wish. These webinars will be recorded and made available on YouTube for asynchronous viewing. We’ll be announcing the first webinar soon, so stay tuned!

-

We plan to release a summary preprint detailing the challenge results, and all challenge participants on the final leaderboard are invited to be co-authors.

OpenADMET is committed to advancing ADMET predictive modeling and will continue to host blind challenges quarterly. Please complete this survey with your contact information and any feedback on the recent challenge. This information will be used to send invitations to the upcoming webinar series. We will also be announcing our next blind challenge shortly!

Please also indicate whether you want to be included as a co-author, and fill out your name and affiliation, as you want it to appear in the paper. Importantly, even if you have already provided your contact information with your submission, please re-enter it in the survey so we have a centralized database.

Questions or Ideas?

We’d love to hear from you! Whether you want to learn more, have ideas for future challenges, or wish to contribute data to our efforts.

Join the OpenADMET Discord or contact us at openadmet@omsf.io.

Let’s work together to transform ADMET modeling and accelerate drug discovery!

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Jon Ainsley, Andrew Good, Elyse Bourque, Lakshminarayana Vogeti, Renato Skerlj, Tiansheng Wang, and Mark Ledeboer for generously providing the Expansion Therapeutics dataset used in this challenge as an in-kind contribution.